Rate-independent plasticity is characterized by the irreversible straining that occurs in a material once a certain level of stress is reached. The plastic strains are assumed to develop instantaneously (that is, independent of time). Several options are available to characterize different types of material behaviors:

Material Behavior Option

Bilinear Isotropic Hardening

Multilinear Isotropic Hardening

Nonlinear Isotropic Hardening

Classical Bilinear Kinematic Hardening

Multilinear Kinematic Hardening

Nonlinear Kinematic Hardening

Anisotropic

Extended Drucker-Prager

Extended Drucker-Prager Cap

Cast Iron

User-specified behavior (described in User Routines and Non-Standard Uses)

Except for user-specified behavior (TB,USER), each material-behavior option is described in greater detail later in this chapter. Figure 4.1: Stress-Strain Behavior of Each of the Plasticity Options represents the stress-strain behavior of each of the options.

Plasticity theory provides a mathematical relationship that characterizes the elastoplastic response of materials. There are three ingredients in the rate-independent plasticity theory: the yield criterion, flow rule and the hardening rule. Table 4.1: Notation summarizes the notation used in the remainder of this chapter.

The yield criterion determines the stress level at which yielding is

initiated. For multi-component stresses, this is represented as a

function of the individual components, , which can be interpreted as an equivalent stress

:

(4–4) |

where:

Table 4.1: Notation

| Variable | Definition | Mechanical APDL Output Label |

|---|---|---|

| elastic strains | EPEL | |

| plastic strains | EPPL | |

| trial strain | ||

|

| equivalent plastic strain | EPEQ |

| stresses | S | |

| equivalent stress | ||

| material yield parameter | ||

| mean or hydrostatic stress | HPRES | |

|

| equivalent stress parameter | SEPL |

| plastic multiplier | ||

| yield surface translation | ||

| plastic work | ||

| translation multiplier | ||

| stress-strain matrix | ||

| tangent modulus | ||

| yield criterion | ||

| stress ratio | SRAT | |

| plastic potential | ||

| deviatoric stress |

When the equivalent stress is equal to a material yield parameter σy,

(4–5) |

the material will develop plastic strains. If is less than

, the material is elastic and the stresses will

develop according to the elastic stress-strain relations. Note that

the equivalent stress can never exceed the material yield since in

this case plastic strains would develop instantaneously, thereby

reducing the stress to the material yield. Equation 4–5 can be plotted in stress space as

shown in Figure 4.2: Various Yield Surfaces for some of the plasticity

options. The surfaces in Figure 4.2: Various Yield Surfaces are known as

the yield surfaces and any stress state inside the surface is

elastic, that is, they do not cause plastic strains.

The flow rule determines the direction of plastic straining and is given as:

(4–6) |

where:

If is the yield function (as is normally assumed),

the flow rule is termed associative and the plastic strains occur in

a direction normal to the yield surface.

The hardening rule describes the changing of the yield surface with progressive yielding, so that the conditions (stress states) for subsequent yielding can be established. Two hardening rules are available: work (or isotropic) hardening and kinematic hardening. In work hardening, the yield surface remains centered about its initial center line and expands in size as the plastic strains develop. For materials with isotropic plastic behavior this is termed isotropic hardening and is shown in Figure 4.3: Types of Hardening Rules (a). Kinematic hardening assumes that the yield surface remains constant in size and the surface translates in stress space with progressive yielding, as shown in Figure 4.3: Types of Hardening Rules (b).

The yield criterion, flow rule and hardening rule for each option are summarized in Table 4.2: Summary of Plasticity Options and are discussed in detail later in this chapter.

Table 4.2: Summary of Plasticity Options

| Name | TB Lab | Yield Criterion | Flow Rule | Hardening Rule | Material Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilinear Isotropic Hardening | PLASTIC

(TBOPT = BISO) | von Mises/Hill | associative | work hardening | bilinear |

| Nonlinear Isotropic Hardening | NLISO | von Mises/Hill | associative | work hardening | nonlinear |

| Classical Bilinear Kinematic Hardening | PLASTIC

(TBOPT = BKIN) | von Mises/Hill | associative (Prandtl-Reuss equations) | kinematic hardening | bilinear |

| Nonlinear Kinematic Hardening | CHAB | von Mises/Hill | associative | kinematic hardening | nonlinear |

| Extended Drucker-Prager | EDP | von Mises with dependence on hydrostatic stress | associative or non-associative | work hardening | multilinear |

| Cast Iron | CAST | von Mises with dependence on hydrostatic stress | non-associative | work hardening | multilinear |

| Gurson | GURS | von Mises with dependence pressure and porosity | associative | work hardening | multilinear |

If the equivalent stress calculated using elastic properties exceeds the material yield, then plastic straining must occur. Plastic strains reduce the stress state so that it satisfies the yield criterion, Equation 4–5. Based on the theory presented in the previous section, the plastic strain increment is readily calculated.

The hardening rule states that the yield criterion changes with work hardening and/or with kinematic hardening. Incorporating these dependencies into Equation 4–5, and recasting it into the following form:

(4–7) |

where:

and

are termed internal or state variables.

Specifically, the plastic work is the sum of the plastic work done

over the history of loading:

(4–8) |

where:

and translation (or shift) of the yield surface is also history dependent and is given as:

(4–9) |

where:

Equation 4–7 can be differentiated so that the consistency condition is:

(4–10) |

Noting from Equation 4–8 that

(4–11) |

and from Equation 4–9 that

(4–12) |

Equation 4–10 becomes

(4–13) |

The stress increment can be calculated via the elastic stress-strain relations

(4–14) |

where:

with

(4–15) |

since the total strain increment can be divided into an elastic and plastic part. Substituting Equation 4–6 into Equation 4–13 and Equation 4–15 and combining Equation 4–13, Equation 4–14, and Equation 4–15 yields

(4–16) |

The size of the plastic strain increment is therefore related to the total increment in strain, the current stress state, and the specific forms of the yield and potential surfaces. The plastic strain increment is then calculated using Equation 4–6:

(4–17) |

An Euler backward scheme is used to enforce the consistency condition Equation 4–10. This ensures that the updated stress, strains and internal variables are on the yield surface. The algorithm proceeds as follows:

The material parameter

Equation 4–5 is determined for this time step (for example, the yield stress at the current temperature).

The stresses are calculated based on the trial strain

, which is the total strain minus the plastic strain from the previous time point (thermal and other effects are ignored):

(4–18)

where the superscripts are described with Understanding Theory Reference Notation and subscripts refer to the time point. Where all terms refer to the current time point, the subscript is dropped. The trial stress is then

(4–19)

The equivalent stress

is evaluated at this stress level by Equation 4–4. If

is less than

, the material is elastic and no plastic strain increment is calculated.

If the stress exceeds the material yield, the plastic multiplier

is determined by a local Newton-Raphson iteration procedure (Simo and Taylor([156])).

is calculated via Equation 4–17.

The current plastic strain is updated

(4–20)

where:

= current plastic strains (output as EPPL)

and the elastic strain calculated

(4–21)

where:

= elastic strains (output as EPEL)

The stress vector is:

(4–22)

where:

= stresses (output as S)

The increments in the plastic work

and the center of the yield surface

are calculated via Equation 4–11 and Equation 4–12 and the current values updated

(4–23)

and

(4–24)

where the subscript n-1 refers to the values at the previous time point.

For output purposes, an equivalent plastic strain

(output as EPEQ), equivalent plastic strain increment

(output with the label "MAX PLASTIC STRAIN STEP"), equivalent stress parameter

(output as SEPL) and stress ratio

(output as SRAT) are calculated. The stress ratio is given as

(4–25)

where

is evaluated using the trial stress .

is therefore greater than or equal to one when yielding is occurring and less than one when the stress state is elastic. The equivalent plastic strain increment is given as:

(4–26)

The equivalent plastic strain and equivalent stress parameters are developed for each option in the next sections.

Note that the Euler backward integration scheme in step 4 is the radial return algorithm (Krieg([47])) for the von Mises yield criterion.

The tangent or elastoplastic stress-strain matrix is derived from the

local Newton-Raphson iteration scheme used in step 4 above (Simo and

Taylor([156])). It is therefore the

consistent (or algorithmic) tangent. If the flow rule is

nonassociative (), then the tangent is unsymmetric.

These options use the von Mises yield criterion with the associated flow rule and isotropic (work) hardening (accessed via TB,PLASTIC,,,,BISO).

The equivalent stress Equation 4–4 is:

(4–27) |

where {s} is the deviatoric stress Equation 4–37.

When is equal to the current yield stress

the material is assumed to yield. The yield

criterion is:

(4–28) |

For work hardening, is a function of the amount of plastic work done.

For the case of isotropic plasticity assumed here,

can be determined directly from the equivalent

plastic strain

of Equation 4–43 (output as

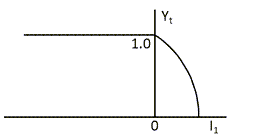

EPEQ) and the uniaxial stress-strain curve as depicted in Figure 4.4: Uniaxial Behavior.

is output as the equivalent stress parameter

(output as SEPL).

Both the Voce([253]) hardening law, and the nonlinear power hardening law can be used to model nonlinear isotropic hardening. The Voce hardening law for nonlinear isotropic hardening behavior (accessed with TB,NLISO,,,,VOCE) is specified by the following equation:

(4–29) |

where:

|

|

The constitutive equations are based on linear isotropic elasticity, the von Mises yield function and the associated flow rule. The yield function is:

(4–30) |

The plastic strain increment is:

(4–31) |

where:

The equivalent plastic strain increment is then:

(4–32) |

The accumulated equivalent plastic strain is:

(4–33) |

The power hardening law for nonlinear isotropic hardening behavior (accessed with TB,NLISO,,,,POWER) which is used primarily for ductile plasticity and damage is developed in the Gurson's Model:

(4–34) |

where:

is the microscopic equivalent plastic strain and

is defined by:

(4–35) |

where:

|

|

| |

This option uses the von Mises yield criterion with the associated flow rule and kinematic hardening (TB,PLASTIC,,,,BKIN).

The equivalent stress Equation 4–4 is therefore:

(4–36) |

| where |

(4–37) |

where:

| |

Because Equation 4–36 is dependent on the

deviatoric stress, yielding is independent of the hydrostatic stress

state. When is equal to the uniaxial yield stress,

, the material is assumed to yield. The yield

criterion Equation 4–7 is

therefore:

(4–38) |

The associated flow rule yields:

(4–39) |

so that the increment in plastic strain is normal to the yield surface. The associated flow rule with the von Mises yield criterion is known as the Prandtl-Reuss flow equation.

The yield surface translation is defined as:

(4–40) |

where:

The shift strain is calculated analogously to Equation 4–24:

(4–41) |

where:

|

|

(4–42) |

where:

The yield surface translation is initially zero and changes with subsequent

plastic straining.

The equivalent plastic strain is dependent on the loading history and is defined to be:

(4–43) |

where:

|

|

|

|

The equivalent stress parameter is equal to the yield stress.

For bilinear kinematic hardening, shifting the yield center is possible by applying an initial backstress in the yield criteria. The yield function becomes:

(4–44) |

and the associated flow rule is:

(4–45) |

where is the initial backstress (defined via

INISTATE). The equivalent stress

becomes:

(4–46) |

The effective backstress is still constituted according to Rice's hardening rule, which

behaves as a linear relationship with the plastic strain. In

the case of a non-zero initial backstress for this model,

the total backstress

does not maintain a straightforward linear

relationship with the plastic strain. As a result, the yield

center is naturally shifted due to the definition of

.

This option (TB,PLASTIC,,,,KINH) uses the Besseling(54) model, also called the sublayer or overlay model (Zienkiewicz(55)), to characterize the material behavior. The material behavior is assumed to be composed of various portions (or subvolumes), all subjected to the same total strain, but each subvolume having a different yield strength. (For a plane stress analysis, the material can be thought to be made up of a number of different layers, each with a different thickness and yield stress.) Each subvolume has a simple stress-strain response but when combined the model can represent complex behavior. This allows a multilinear stress-strain curve that exhibits the Bauschinger (kinematic hardening) effect (Figure 4.1: Stress-Strain Behavior of Each of the Plasticity Options (b)).

The following steps are performed in the plasticity calculations:

The portion of total volume for each subvolume and its corresponding yield strength are determined.

The increment in plastic strain is determined for each subvolume assuming each subvolume is subjected to the same total strain.

The individual increments in plastic strain are summed using the weighting factors determined in step 1 to compute the overall or apparent increment in plastic strain.

The plastic strain is updated and the elastic strain is calculated.

The portion of total volume (the weighting factor) and yield stress

for each subvolume is determined by matching the material response

to the uniaxial stress-strain curve. A perfectly plastic von Mises

material is assumed and this yields for the weighting factor for

subvolume

(4–47) |

where:

The yield stress for each subvolume is given by

(4–48) |

where (,

) is the breakpoint in the stress-strain curve. The

number of subvolumes corresponds to the number of breakpoints

specified.

The increment in plastic strain for each subvolume is calculated using a von Mises

yield criterion with the associated flow rule. The section on

specialization for bilinear kinematic hardening is followed but

since each subvolume is elastic-perfectly plastic,

and therefore

is zero.

The plastic strain increment for the entire volume is the sum of the subvolume increments:

(4–49) |

where:

The current plastic strain and elastic strain can then be calculated for the entire volume via Equation 4–20 and Equation 4–21.

The equivalent plastic strain (output as EPEQ) is defined by Equation 4–43 and equivalent stress parameter

(output as SEPL) is calculated by evaluating the

input stress-strain curve at

(after adjusting the curve for the elastic strain

component). The stress ratio

(output as SRAT, Equation 4–25) is defined using the

and

values of the first subvolume.

The material model considered is a rate-independent version of the nonlinear kinematic hardening model proposed by Chaboche([245], [246]) (accessed via TB,CHABOCHE). The constitutive equations are based on linear isotropic elasticity, a von Mises yield function and the associated flow rule. Like the bilinear hardening option, the model can be used to simulate the monotonic hardening and the Bauschinger effect. The model is also applicable to simulate the ratcheting effect of materials. In addition, the model allows the superposition of several kinematic models as well as isotropic hardening models. It is thus able to model the complicated cyclic plastic behavior of materials, such as cyclic hardening or softening and ratcheting or shakedown.

The model uses the von Mises yield criterion with the associated flow rule, the yield function is:

(4–50) |

where:

According to the normality rule, the flow rule is written:

(4–51) |

where:

The backstress is superposition of several kinematic models

as:

(4–52) |

where:

The evolution of the backstress (kinematic hardening rule) for each component is defined as:

(4–53) |

where:

The associated flow rule yields:

(4–54) |

The plastic strain increment, Equation 4–51 is rewritten as:

(4–55) |

The equivalent plastic strain increment is then:

(4–56) |

The accumulated equivalent plastic strain is:

(4–57) |

The isotropic hardening variable can be defined by:

(4–58) |

where:

The material hardening behavior in Equation 4–50 can also be

defined via bilinear or multilinear isotropic hardening options,

discussed earlier in Bilinear Isotropic Hardening.

The return mapping approach with consistent elastoplastic tangent moduli that was proposed by Simo and Hughes([252]) is used for numerical integration of the constitutive equation described above.

The Chaboche model supports an initial backstress definition (INISTATE,SET,DTYP,BSTR). The yield function in Equation 4–50 becomes:

(4–59) |

Adhering to the Chaboche constitutive framework, only the associated flow rule changes:

(4–60) |

This option is an extension of the linear Drucker-Prager yield

criterion (input with TB,EDP). Both yield surface

and the flow potential, (input with TBOPT

on TB,EDP command) can be taken as linear,

hyperbolic and power law independently, and thus results in either

an associated or nonassociated flow rule. The yield surface can be

changed with progressive yielding of the isotropic hardening

plasticity material options, see hardening rule Figure 4.1: Stress-Strain Behavior of Each of the Plasticity

Options (c) Bilinear Isotropic and (d)

Multilinear Isotropic.

The yield function with linear form (input with

TBOPT = LYFUN) is:

(4–61) |

where:

| |

| |

| |

The yield function with hyperbolic form (input with

TBOPT = HYFUN) is:

(4–62) |

where:

The yield function with power law form (input with

TBOPT = PYFUN) is:

(4–63) |

where:

Similarly, the flow potential for linear form (input with

TBOPT = LFPOT) is:

(4–64) |

The flow potential for hyperbolic form (input with

TBOPT = HFPOT) is:

(4–65) |

The flow potential for power law form (input with

TBOPT = PFPOT) is:

(4–66) |

The plastic strain is defined as:

(4–67) |

where:

| |

When the flow potential is the same as the yield function, the plastic flow rule is associated, which in turn results in a symmetric stiffness matrix. When the flow potential is different from the yield function, the plastic flow rule is nonassociated, and this results in an unsymmetric material stiffness matrix. By default, the unsymmetric stiffness matrix (accessed by NROPT,UNSYM) will be symmetricized.

The cap model focuses on geomaterial plasticity resulting from compaction at low mean stresses followed by significant dilation before shear failure ([383]). A three-invariant cap plasticity model with three smooth yielding surfaces including a compaction cap, an expansion cap, and a shear envelope proposed by Pelessone ([384]) is described here.

Geomaterials typically have much higher triaxial strength in compression than in tension. The cap model accounts for this by incorporating the third-invariant of stress tensor (J3) into the yielding functions.

Introduced first are functions to be used in the cap model, including shear failure envelope function, compaction cap function, expansion cap function, the Lode angle function, and hardening functions. Then, a unified yielding function for the cap model that is able to describe all the behaviors of shear, compaction, and expansion yielding surfaces is derived using the shear failure envelope and cap functions.

The following topics are covered:

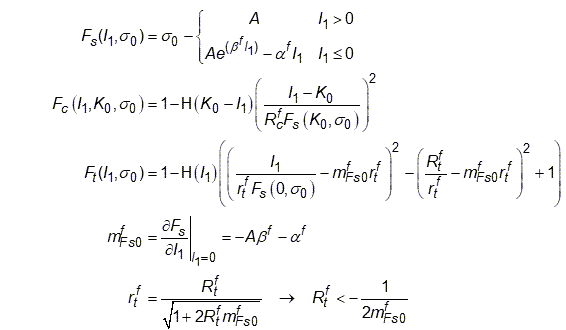

A typical geomaterial shear envelope function is based on the exponential format given below:

(4–68) |

where:

| subscript s = shear envelope function |

| superscript y = yielding related material constants |

TBOPT = CYFUN) |

TBOPT = CYFUN) |

Equation 4–68 reduces to the Drucker-Prager

yielding function if parameter is set to zero. All material constants in

Equation 4–68 are defined based on

and

, which are different from those in the

previous sections. The effect of hydrostatic pressure on

material yielding may be exaggerated at high pressure range

by only using the linear term (Drucker-Prager) in Equation 4–68. Such an exaggeration is reduced by

using both the exponential term and linear term in the shear

function. Figure 4.6: Shear Failure Envelope Functions shows the

configuration of the shear function. In Figure 4.6: Shear Failure Envelope Functions the dots are the testing data

points, the finer dashed line is the fitting curve based on

the Drucker-Prager linear yielding function, the solid

curved line is the fitting curve based on Equation 4–68, and the coarser dashed line is the

limited state of Equation 4–68 at very high

pressures. In the figure

is the current modified cohesion obtained

by setting I1 in Equation 4–68 to zero.

For positive values of , the shear envelope function of the EDP

Cap model is evaluated at

, giving the constant value

.

The compaction cap function is formulated using the shear envelope function defined in Equation 4–68.

(4–69) |

where:

| subscript C = compaction cap-related function or constant |

In Equation 4–69, is an elliptical function combined with

the Heaviside function.

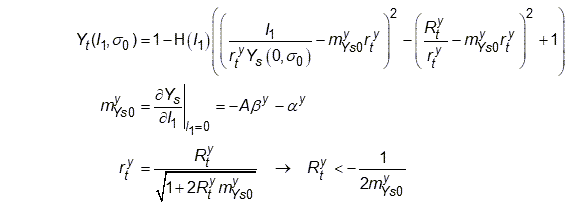

is plotted in Figure 4.7: Compaction Cap Function.

This function implies:

When

, the first invariant of stress, is greater than

, the compaction cap takes no effect on yielding. The yielding may happen in either shear or expansion cap portion.

When

is less than

, the yielding may only happen in the compaction cap portion, which is shaped by both the shear function and the elliptical function.

Similarly, is an elliptical function combined with

the Heaviside function designed for the expansion cap.

is shown in Figure 4.8: Expansion Cap Function.

| (4–70) |

where:

| subscript t = expansion cap-related function or constant |

This function implies that:

When

is negative, the yielding may happen in either shear or compaction cap portion, while the tension cap has no effect on yielding.

When

is positive, the yielding may only happen in the tension cap portion. The tension cap is shaped by both the shear function and by another elliptical function.

Equation 4–70 assumes that is only a function of

and not a function of

as

is set to zero in function

.

Unlike metals, the yielding and failure behaviors of

geomaterials are affected by their relatively weak (compared

to compression) tensile strength. The ability of a

geomaterial to resist yielding is lessened by nonuniform

stress states in the principal directions. The effect of

reduced yielding capacity for such geomaterials is described

by the Lode angle and the ratio

of triaxial extension strength to

compression strength. The Lode angle

can be written in a function of stress

invariants

and

:

(4–71) |

where:

The Lode angle function is defined by:

(4–72) |

where:

The three-invariant plasticity model is formulated by

multiplying in the yielding function by the Lode angle

function described by Equation 4–72. The

profile of the yielding surface in a three-invariant

plasticity model is presented in Figure 4.9: Yielding Surface in π-Plane.

The cap hardening law is defined by describing the evolution

of the parameter , the intersection point of the compaction

cap and the

axis. The evolution of

is related only to the plastic volume

strain

. A typical cap hardening law has the

exponential form proposed in Fossum and Fredrich([93]):

(4–73) |

where:

|

|

Parameters and

have units of 1 / (Force / Length) and 1 /

(Force / Length)2, respectively.

All constants in Equation 4–73 are

non-negative.

Besides cap hardening, another hardening law defined for the

evolution of the cohesion parameter used in the shear

portion described in Equation 4–68 is

considered. The evolution of the modified cohesion

is assumed to be purely shear-related and

is the function of the effective deviatoric plastic strain

:

(4–74) |

The effective deviatoric plastic strain is defined by its rate change as

follows:

(4–75) |

where:

| |

The unified and compacted yielding function for the cap model with three smooth surfaces is formulated using above functions as follows:

(4–76) |

where:

Again, the parameter is the intersection point of the

compaction cap and the

axis. The parameter

is the state variable and can be

implicitly described using

and

given below:

(4–77) |

The yielding model described in Equation 4–76

is used and is drawn in the and

plane in Figure 4.10: Cap Model.

The cap model also allows non-associated models for all compaction cap, shear envelope, and expansion cap portions. The nonassociated models are defined through using the yielding functions in Equation 4–76 as its flow potential functions, while providing different values for some material constants. It is written below:

(4–78) |

where:

| (4–79) |

where:

| superscript f = flow-related material constant |

This document refers to the work of Schwer ([385]) and Foster ([386]) for the numerical formulations used in the Pelessone ([384]) smooth cap plasticity model. Ansys, Inc. developed a new material integrator that is able to achieve a faster convergence rate for the transition zone between the cap and shear portions.

The flow functions in Equation 4–78 and Equation 4–79 are obtained by replacing ,

,

, and

in Equation 4–76 and Equation 4–77 with

,

,

, and

. The nonassociated cap model is input by

using TB,EDP with

TBOPT = CFPOT.

Shear hardening can be taken into account on by providing

(via TB,PLASTIC or

TB,NLISO). The initial value of

must be consistent to

. This input regulates the relationship

between the modified cohesion and the effective deviatoric

plastic strain.

As the smooth models have more numerical advantages, it is often necessary to transfer nonsmooth caps such as the Sandler model ([383]) to a smooth model. To facilitate the model transformation from the nonsmooth cap model to the Pelessone smooth cap model ([384]), two simple and robust methods are used ([387]); rather than solving a group of nonlinear equations, the Ansys, Inc. implementation solves only one scalar nonlinear equation.

Calibrating CAP Constants

Calibrating the CAP constants ,

,

,

,

,

and the hardening input for

differs significantly from the other EDP

options. The CAP parameters are all defined in relation to

and

, while the other EDP coefficients are

defined according to

and

.

The Gurson model is used to represent plasticity and damage in ductile porous metals. The model theory is based on Gurson([363]) and Tvergaard and Needleman([364]). When plasticity and damage occur, ductile metal goes through a process of void growth, nucleation, and coalescence. Gurson’s method models the process by incorporating these microscopic material behaviors into macroscopic plasticity behaviors based on changes in the void volume fraction (porosity) and pressure. A porosity index increase corresponds to an increase in material damage, which implies a diminished material load-carrying capacity.

The microscopic porous metal representation in Figure 4.11: Growth, Nucleation, and Coalescence of Voids in Microscopic Scale(a), shows how the existing voids dilate (a phenomenon, called void growth) when the solid matrix is in a hydrostatic-tension state. The solid matrix portion is assumed to be incompressible when it yields, therefore any material volume growth (solid matrix plus voids) is due solely to the void volume expansion.

The second phenomenon is void nucleation which means that new voids are created during plastic deformation. Figure 4.11: Growth, Nucleation, and Coalescence of Voids in Microscopic Scale(b), shows the nucleation of voids resulting from the debonding of the inclusion-matrix or particle-matrix interface, or from the fracture of the inclusions or particles themselves.

The third phenomenon is the coalescence of existing voids. In this process, shown in Figure 4.11: Growth, Nucleation, and Coalescence of Voids in Microscopic Scale(c), the isolated voids establish connections. Although coalescence may not discernibly affect the void volume, the load carrying capacity of this material begins to decay more rapidly at this stage.

The evolution equation of porosity is given by

(4–80) |

where:

|

|

The evolution of the microscopic equivalent plastic work is:

(4–81) |

where:

|

|

| |

The evolution of porosity related to void growth and nucleation can be stated in terms of the microscopic equivalent plastic strain, as follows:

(4–82) |

where:

The void nucleation is controlled by either the plastic strain or stress, and is assumed to follow a normal distribution of statistics. In the case of strain-controlled nucleation, the distribution is described in terms of the mean strain and its corresponding deviation. In the case of stress-controlled nucleation, the distribution is described in terms of the mean stress and its corresponding deviation. The porosity rate change due to nucleation is then given as follows:

(4–83) |

where:

| |

| |

| |

It should be noted that "stress controlled nucleation"

means that the void nucleation is determined by the maximum normal

stress on the interfaces between inclusions and the matrix. This

maximum normal stress is measured by . Thus, more precisely, the "stress"

in the mean stress

refers to

. This relationship better accounts for the effect

of triaxial loading conditions on nucleation.

Given Equation 4–80 through Equation 4–83, the material yielding rule of the Gurson model is defined as follows:

(4–84) |

where:

| |

, the Tvergaard-Needleman function is:

(4–85) |

where:

The Tvergaard-Needleman function is used to model the loss of material

load carrying capacity, which is associated with void coalescence.

When the current porosity reaches a critical value

, the material load carrying capacity decreases

more rapidly due to the coalescence. When the porosity

reaches a higher value

, the material load carrying capacity is lost

completely. The associative plasticity model for the Gurson model

has been implemented.

Gurson's model accounts for hydrostatic pressure and material isotropic hardening effects on porous metals. The Chaboche model is essentially the von Mises plasticity model incorporating Chaboche-type kinematic hardening.

The Gurson-Chaboche model, also used for modeling porous metals, is an extension of the Gurson model, combining both material isotropic and kinematic hardening. The model is based on the work of Mϋhlich and Brocks ([427]).

The yielding function of the Gurson-Tvergaard and Needleman model is modified as follows:

(4–86) |

where:

is the total effective backstress, and the

total backstress

is the summation of several

sub-backstresses:

where the evolution of each sub-backstress is defined by the Chaboche kinematic law:

(4–87) |

The evolution of the equivalent plastic strain is defined through:

This model first requires the input parameters for Gurson plasticity with isotropic hardening, and then additional input parameters for Chaboche kinematic hardening. For more information, see Hardening in the Material Reference.

The cast iron plasticity model is designed to model gray cast iron. The microstructure of gray cast iron can be looked at as a two-phase material, graphite flakes inserted into a steel matrix (Hjelm([334])). This microstructure leads to a substantial difference in behavior in tension and compression. In tension, the material is more brittle with low strength and cracks form due to the graphite flakes. In compression, no cracks form, the graphite flakes behave as incompressible media that transmit stress and the steel matrix only governs the overall behavior.

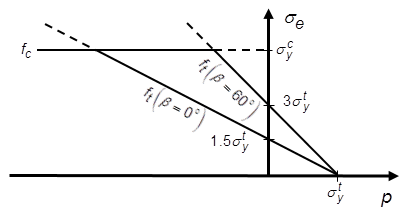

The model assumes isotropic elastic behavior, and the elastic behavior is assumed to be the same in tension and compression. The plastic yielding and hardening in tension may be different from that in compression. (See Figure 4.12: Idealized Response of Gray Cast Iron in Tension and Compression.)

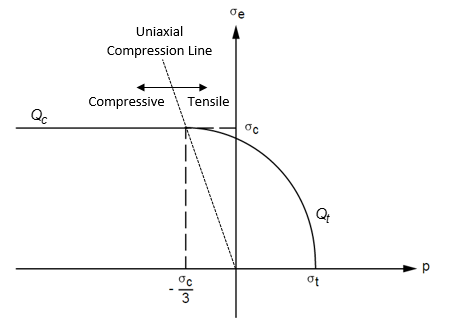

Yield Criteria

A composite yield surface is used to describe the different behavior in tension and compression. The tension behavior is pressure-dependent and the Rankine maximum stress criterion is used. The compression behavior is pressure-independent and the von Mises yield criterion is used. In principal stress space, the yield surface is a cylinder with a tension cutoff (cap). Figure 4.13: Cross-Section of Yield Surface shows a cross section of the yield surface on principal deviatoric-stress space and Figure 4.14: Yield Surface in the Meridional Plane shows the composite yield surface in the meridional plane.

The yield surface for tension and compression "regimes" are described by Equation 4–88 and Equation 4–89 (Chen and Han([332])).

The yield function for the tension cap is:

(4–88) |

and the yield function for the compression regime is:

(4–89) |

where:

| |

| |

| |

| |

Flow Rule

The plastic strain increments are defined as:

(4–90) |

where is the so-called plastic flow potential, which

consists of the von Mises cylinder in compression and modified to

account for the plastic Poisson's ratio in tension, and takes the

form:

(4–91) |

(4–92) |

where:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Experimental evidence suggests that is always less than 0.5. For

= 0.5, Equation 4–92 reduces to

the von Mises cylinder. The flow potentials in the meridional plane

are shown in this figure:

The region to the left of the uniaxial compression line is the compressive flow potential, while the region to the right is the tensile flow potential. As the flow potential is different from the yield function (nonassociated flow rule), the resulting material Jacobian is unsymmetric.

Hardening

The yield stress in uniaxial tension, , depends on the equivalent uniaxial plastic strain

in tension,

, and the temperature

. Also the yield stress in uniaxial compression,

, depends on the equivalent uniaxial plastic strain

in compression,

, and the temperature

.

To calculate the change in the equivalent plastic strain in tension, the plastic work expression in the uniaxial tension case is equated to general plastic work expression as:

(4–93) |

where:

|

|

The change in the equivalent plastic strain in compression is defined as:

(4–94) |

where:

|

|