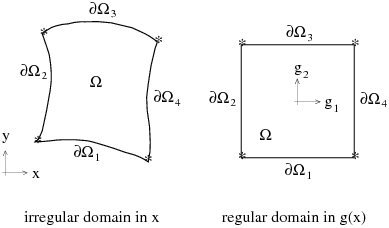

The transformation maps a parent domain into a deformed domain. The transformation

begins with the construction of a global coordinate system, defined on a simply

shaped domain. These global coordinates represent a mapping of the

irregularly-shaped computational domain into a regular parent domain (such as a

square in 2D or a cube in 3D). For example, the irregular domain shown in Figure 15.3: Thompson Transformation is

mapped onto a square by the global-coordinates transformation function

. The coordinates

have the same number of components as the mesh coordinates

.

In the 2D case shown in Figure 15.3: Thompson Transformation,

the global coordinates are constructed on the basis of the following equation:

(15–6) |

with the following boundary conditions:

(15–7) |

The Thompson transformation for this example is simply the inverse mapping

. Once

has been constructed, the Thompson transformation is the solution

that satisfies Equation 15–6

with appropriate boundary conditions. The calculation of the

field, as well as the Thompson transformation itself, is solved by

standard finite-element techniques.

Equation 15–6

is linear in , but not in

. The Thompson transformation is inherently nonlinear in

, even though the Laplacian is a linear operator. The construction

of the

field is performed only once at the beginning of the simulation,

before the main solver starts. The Thompson transformation is then solved in a

coupled fashion, together with the equations governing the flow.

The choice of boundary conditions given to and

in the Thompson transformation governs the remeshing itself. The

Thompson transformation is applied to the remeshing subdomain. Each separate

sub-boundary of the remeshing subdomain is referred to as a segment. On each

segment, one component of the vector

(essential boundary condition) must be specified, while a

zero-normal-derivative condition (natural boundary condition) is applied to the

other component(s).